Curved, enveloping lines, mute and earthen shades inspired by nature, geometries that never penalize comfort, even when they become more daring, imaginative variations on interlacing cords or fibers: these are the salient features of the outdoor offerings presented at the fair by companies in the sector. Here we tell you all about them

Bjarke Ingels: we create hybrid projects for future generations

Bjarke Ingels

The architect helming the Big Group talks about his latest twin-soul projects, such as the Copenhill waste-to-energy plant/ski slope and the museum/bridge in Kistefos Art Park. They represent “new typologies,” opening the way for those who follow after us in a changing world.

Bjarke Ingels, with his Big Group, aims to be the architect of hybrids, of the urban waste-to-energy plant that has been turned into a ski slope in Copenhagen, a factory for a furnishing company (Norway’s Vestre) built in a forest that is also a tourist destination. A speaker at the recent “supersalone,” his Open Talk lecture was devoted to the latest projects by his studio, including Citywave, in Milan, inside CityLife: a curved structure, covered with solar panels that will connect two office blocks like a large portico. Work began last September, but Ingels’ challenges seem to know no end.

City Life, Milan. Image by BIG

We’re witnessing the decolonisation of the built environment and of society as a whole – a huge transformation. Many of the projects we’re working on are a departure from the classical architecture of museums and concert halls. We are designing a large plastic recycling plant in the US, for example, and an island that runs on wind power. There are no pure design solutions for all this. We need to work together on financial design and engineering – lots of different fields converge in our projects. As designers we have a key role to play, tying together different aspects into something holistic.

Le Corbusier said that the role of architects was to invent new typologies so that market forces can pursue them in order to refine and optimise them. I think that, in this sense, a museum that is a bridge (Twist, for the Kistefos Art Park in Norway, Ed.) and the waste-to-energy plant that is a ski slope (Copenhill in Copenhagen, Ed.) are new typologies – hybrids that unite things that had never been seen together before. They are a sort of gift that we can hand down to future generations. The first new thing is always the most difficult. It may not be the best, but it opens the door for someone else who is capable of improving it. The Danish architect Arne Jacobsen, wasn’t exactly an innovator. For many of the things he achieved, Mies van der Rohe and others had opened the way for him. But he was so great at perfecting them, at improving them, at making them more elegant. I imagine our role will consist of trying to build hybrids for the first time, so that others can use them as a starting point.

The Plus Rooftop, BIG for Vestre. Image by Lucian R

It has accelerated some transformations: the move from physical to digital, for example. E-commerce has made classic static shops less attractive from a financial point of view. Now that they’re no longer full of shops, what are we to do with the ground floors of our cities to make them livelier and more inviting? There must be more interesting solutions. We’ve started to look at public spaces, like the squares where markets are held on Saturdays and Sundays. There’s room for new typologies, like pop-up shops and markets, that enliven public places, even if they’re not there all the time. We’ve started thinking about how mobile autonomous infrastructures could be part of dynamic and nomadic open spaces in the future.

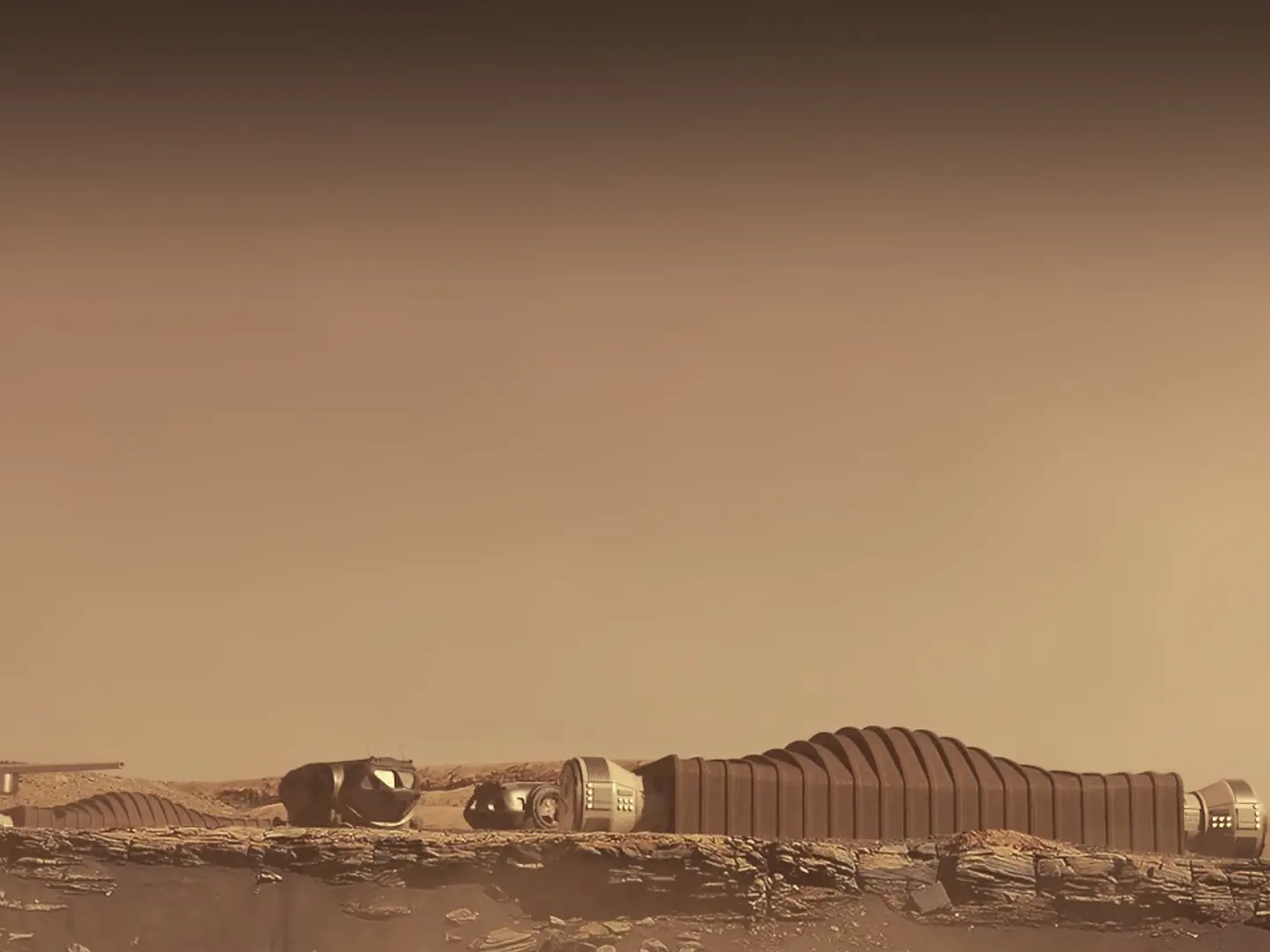

Mars Dune Alpha, CHAPEA program. BIG for NASA

The Telosa project we’re working on (with former Wallmart president Marc Lore Ed.) could be a response to the gentrification problem that often leads to displacement. Rehabilitation is a good thing for districts, because they become more desirable, but they also become more expensive. This means that people who originally lived there can no longer afford to do so. Improving districts should also mean that they cater for everyone, not just the latest arrivals.

We’re building 3D-printed habitats for NASA in Texas (the Mars Dune Alpha Project, Ed.). I think the first step will be the Moon. The Olympus programme will deliver a permanent base to the Moon’s South Pole by the end of this decade. I really believe it will be under construction by the late 2020s. I don’t doubt either that there will be a permanent human presence on the Moon and on Mars in our lifetime. We will be able to exploit the underground lava tubes several kilometres long on the Moon, and start by building a small inflatable base there, because they will protect us from the meteors and from radiation. Once they’re closed off, they can be filled with breathable air. In order to live on another planet we will have to go back to being cavemen.

Mars Dune Alpha, CHAPEA program. BIG for NASA